Never Sell the Land

NORA CRIST, CLARK’S FARM

ELLICOTT CITY, MARYLAND

How big is 540 acres? Technically, about 0.84 square miles. Almost 410 football fields in size. In other words: big. Very, very big. It was on these five hundred and forty sprawling, lush, beautiful acres in now-affluent Howard County, Maryland, that Nora Crist grew up and now farms.

Nora is an experienced and knowledgeable 28-year-old farmer who never planned to be a farmer. She’s a dynamo, a gifted grower of beautiful vegetables, a smart businesswoman, and a ton of fun to hang out with, if you can keep up with her. She talks and moves a mile a minute.

Nora was born into a long lineage of farmers and landowners, and she is now the 7th generation. Multiple branches of her family have been farming in Howard County since 1797, and their roots run deep in the history of the area. (Nora’s story is almost the opposite of Shannon Varley’s, whose search to own her own farm you can read here.) It’s important to understand a bit of the more recent history of Clark’s Farm to appreciate Nora’s story. Her story is stitched from the story of the farm itself, one that Nora seems to relish telling.

The growth of the farm

Nora’s ancestors on her mother’s side farmed in various locations around the county. In 1927 her great-grandfather purchased the farm where Nora currently lives, Clark’s Elioak Farm, and he raised Angus cattle. When his son, Nora’s grandfather, returned from service in WWII, he purchased the farm from his father and started a dairy operation. He also had “what everyone had in those days,” says Nora: chickens, pigs, beef cows, and the milking cows. “And that was their monthly paycheck.”

His eldest son, Nora’s uncle, took over the dairy operation some time in the 1970s and expanded it. Nora’s grandfather pretty much retired from farming at that point. He turned his attention to serving in the Maryland State Senate, and during his tenure there he helped develop the Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Foundation, a program that promotes agriculture and preserves farmland. That program is one of the most successful programs of its kind in the country. The state of Maryland has preserved in perpetuity more agricultural land than any other state.

A large memorial stone on the farm bears the words of Nora’s grandfather: Never sell the land. Clark’s Elioak Farm will remain farmland and never be developed.

The farm changes

As the Columbia area in Howard County became more suburban, it got harder to run the farm. Harder as in getting machinery down the road from field to field, or farm supply stores moving farther out. In the mid 1990s, when she was 5, Nora’s uncle moved the entire dairy operation to southern Georgia, which was a better place to expand. Now with the dairy operation gone, her grandfather found himself back in charge of the farm. The farm got by with what was left—some beef cattle, some hay and soybeans, and a roadside farm stand that had been selling sweet corn and tomatoes every summer since the 1960s. That farm stand plays heavily in the unfolding of Nora’s journey. The farm got by, but it was not a model of a vibrant, growing enterprise.

Nora’s brilliant mother

Nora’s mother, Martha, did not consider herself a farmer. She had married the local Southern States dealer and worked part-time in his store. They lived on a small farm right next door to her father’s farm (Nora’s grandfather’s) and raised Nora and her brother, who both grew up riding horses and running around like farm kids.

Nora’s job as a young girl was to help out at the family farm stand. She learned at a young age how to make change and how to interact with customers. She says she loved working there because it was a fun place to be and she got to hang out with her grandparents.

Things ticked along until 2000, when Nora’s dad passed away. She was only 12.

Martha—“always at the forefront of things,” says Nora—did not want to run her husband’s business, so she hatched a plan that, like the farm stand, would turn out to play a big role in Nora’s development. It was a brilliant plan that created tremendous value out of an asset she already had—land.

With the blessing of her father (Nora’s grandfather), Martha decided in 2002 to turn about 20 acres of the farm into a petting farm, where kids could come for hay rides, interact with animals, and have their birthday parties. The area around the Clark farm had become even more suburban, and the next generation of kids was growing up completely removed from farm life; no longer did kids spend their summers on their grandparents’ farms. Martha felt that a petting farm would be a way to get kids back on a farm.

Nora goes to work

Fourteen years old when it opened, Nora worked at the petting farm giving pony rides and helping with the animals. During the summers of her junior and senior years in high school, she also took over the management of the produce stand, and she developed great confidence in that role. She was able to make decisions about how the stand operated, and she got a percentage of the proceeds, which was great incentive for her to sell, sell, sell!

In between her duties at the stand and the petting farm, she would go horseback riding, her real passion.

I love Nora’s description of growing up and deciding what to do with one’s life: “You grow up, you move out of your parents’ house, and you go do something.” She didn’t grow up with the attitude of “get me out of here!” but she also never considered farming as a career option. She was only 5 years old when her uncle moved the dairy operation, and the little bit of farming done by her grandfather didn’t make a lot of money, so she didn’t have a vision of how to make a living off the farm. “What would I do on the farm?” Nora says.

So off she went to college to study equine business. She had thought she might some day end up back on the farm as a place to live, but not before traveling far and wide, working on other people’s horse farms.

Command central for Nora’s farm business

But then something happened that threw her off course. During her first semester in college in 2005, Nora started experiencing joint pain, specifically in her hands and wrists. Doctors weren’t sure what was causing the pain, and it kept getting worse. She was having trouble using her hands and walking. By January every joint in her body was constantly throbbing. She pushed through, thinking at some point the pain would go away.

But it didn’t, and in March of her freshman year she finally received a diagnosis: rheumatoid arthritis (RA). She was told that RA was chronic and incurable but that she would be able to manage the disease and the pain with medication.

Nora was terrified. She was 18 years old with big plans to work with horses, but instead was given a lifetime sentence of a painful disease. And Nora’s arthritis was a severe case. She told me she never cried much growing up, but now she cried a lot, daily. She cried from the pain and from not knowing if she’d ever be without pain again. She didn’t know how she was going to live her dream of working with horses, much less even function in school.

She says she just tried to continue with her life, but everything hurt: opening a door, brushing her teeth, getting dressed. She hurt just as much sitting still as moving, and moving was difficult. She couldn’t walk fast, and she had trouble holding a pencil. She wore her hair down for a year because she wasn’t able to put it up.

She didn’t want to tell people what was going on with her for fear they’d treat her differently. She also had the feeling that telling people would make it real. Her roommate knew and one teacher who Nora was close to, but that’s all.

Returning home

Nora’s plan had been to secure a summer job on a horse farm, and she was excited by the prospect of going anywhere she could find a job. But with her horrible pain, finding a job didn’t seem likely. “What would I say? ‘I have crippling rheumatoid arthritis but can I come work with your horses for the summer?’” Instead, she came back home that summer after her freshman year and again managed the produce stand that she had managed while in high school. She was in considerable pain and needed to have support around her in case she wasn’t able to function physically.

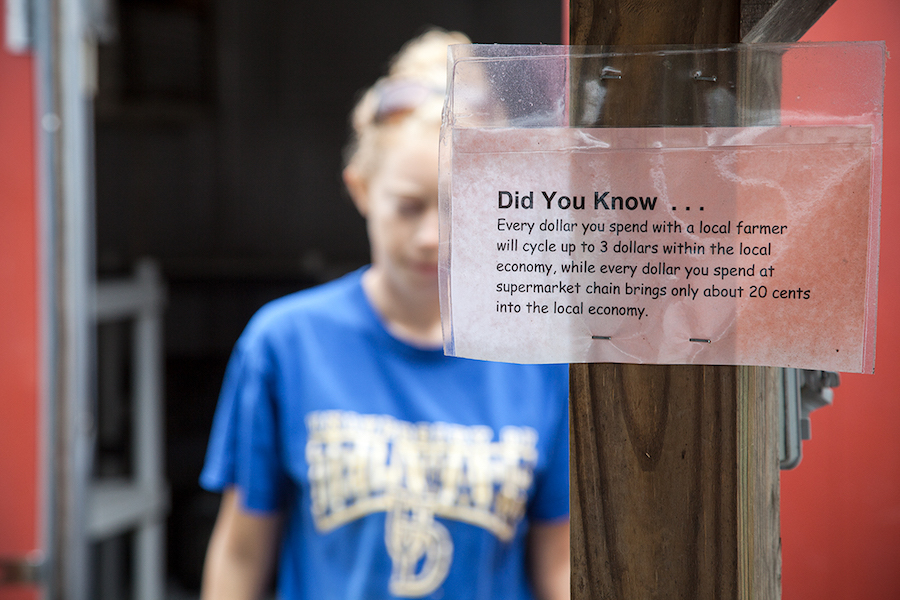

Nora waits for customers at the family farm stand

Somehow she managed to make it to the stand every day. Each evening she would take the cash drawer to her grandfather, who at that point was near the end of his life and didn’t leave the house much. She would bring him some corn and a ripe tomato and let him know which customers stopped by and asked about him. Together they would count the drawer. (That’s such a sweet image, and one I wish I could have photographed.) This was their routine every night of the summer, until he passed away at the end of August.

Nora says that despite her crippling pain, that summer’s experience held a silver lining. “If I hadn’t had my disease and I had gone somewhere else for the summer, then I wouldn’t have had that time as an adult to get to know my grandfather. I also started to grow up and realize that the farm was not something that was holding me back or holding me down, but it might be a gift, it might be something I’d appreciate. I didn’t want to see coming back to the farm as a safety net, I wanted to see it as something I wanted, and that summer it became an option.”

“I joke now that I didn’t see farming as an option or a career when I was in high school. Nobody farmed. You didn’t meet farmers, and if you did they were 60-year-old men who just sat on tractors all day. Doctor, lawyer, nurse, teacher…those were careers. But I started to see farming as something I would enjoy, something I could do.”

The medical treatment

Essentially Nora’s treatment for the RA was prednisone, over-the-counter anti-inflammatories, and the least detrimental of a class of medicines known as disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). She had to start at the lowest level of a DMARD and take it for a while to see if it would help. If it gave no relief, she would have to raise the dosage. Nora says it was like a waiting game. When the medicine failed to bring relief, she would again up the dosage until she reached the maximum amount, then she’d move on to a more powerful drug. Soon she was taking Methotrexate, a drug used to suppress the immune system. It’s a chemotherapy drug used for autoimmune diseases and cancer. Every six weeks, finding little relief, she upped her dosage, until she was at the maximum oral dosage. She suffered from bouts of nausea, frequent colds, and thinning hair.

But the pain was finally lessening. Nora knew the drugs would have bad side effects, but she felt following her doctor’s recommendations was her only option. As she put it, “As far as I had been told, this was all I could hope for and it would be how my whole life would be, ups and downs, lots and lots of pills, and the possibility of stronger meds down the road.” She loved her rheumatologist, who she found to be very supportive, and she soldiered on.

The return to the farm

After graduation from college in 2009, she returned to the farm with the idea of making farming her career. By then her disease was pretty much under control through her medications.

One of Nora’s goals for the farm was to change how the farm stand worked. The farm grew tomatoes, corn and sweet peppers, and everything else was purchased elsewhere to resell at the stand. But Nora wanted to grow all the vegetables herself and be able to say, “I grew this—I grew all of this.”

Not quite knowing what she was doing, the plan was for the farm manager to teach her; sadly, though, he suffered a stroke and passed away that summer. She was on her own, and definitely out of her comfort zone. She says she was just lucky to meet many people who helped her get through her season.

Over the next few years, she says she learned mostly through trial and error, by asking other farmers, by looking in books, and by searching the Internet. “It’s amazing that I’ve been able to learn hands-on. I make mistakes, and that’s been incredibly valuable to my growth.”

So one day this woman walks into my farm stand

For the next six years, her treatment fluctuated between being under control and needing to step up the medication. After the oral meds came painful injections, and after that came day-long infusions—all with horrible side effects and not much effect on her pain. She was told there was no alternative, so she persevered.

“Knowing that the infusion was horrible and that it was poison, I said to myself, ‘If I’m going to take this horrible medicine for the rest of my life, however long that may be, let me eat healthy and that way I can prolong my body as long as possible.’ But what is healthy? I don’t know what that is. Is it whole grains and what the USDA pyramid says? Is it olive oil? Fish? Vegan? Raw food?”

She ate what she thought was healthy, what she’d grown up on: low fat everything, lots of boneless skinless chicken breast and vegetables, olive oil, rice, pasta, hamburger helper with 90% lean beef.

One day, Nora was engaged in conversation with a customer at the farm stand. She learned that the woman, Gina Rieg, was a certified health coach, and despite Nora’s belief that food coaches were “full of junk,” she liked Gina’s answer to the question What is healthy to eat? “Whole foods, real foods. What our grandparents ate. Butter, cream, pasture-raised meat, and organic vegetables.”

“Whether she’s right or not,” Nora says, “that’s the answer I want.” After some basic diet cleanup, Gina suggested Nora try gluten free. Nora’s thought: “This chick is crazy. She doesn’t know what she’s talking about. I’m not going to go gluten free. I mean…quality of life here, come on.”

The food-body connection

But then an interesting thing happened. One day Nora made some homemade bread and ate just the bread and some crackers all day. The next day her pain was markedly worse, so she decided not to eat any gluten that day. The very next day she felt better, and pain free. It was a light-bulb moment. “Maybe…food…affects…our… body.”

In retrospect she says she can’t believe she didn’t make that connection before. She immediately chose to go gluten free and cleaned out her kitchen and pantry of anything containing gluten.

The switch to gluten free came about two weeks before her next scheduled infusion. She cancelled it. Her doctor scoffed at her and said to call when she was in pain. About two months later she was, indeed, in pain again, but this time, she says emphatically, she called Gina and not her rheumatologist.

Gina suggested she do the GAPS diet, a rigorous diet with the goal of healing an imbalanced gut by focusing on whole foods, healthy fats, bone broth, and fermented foods. The diet is extremely challenging, but Nora was committed to getting healthy. She started immediately, and she stuck with it, despite feeling worse before she felt better and then often experiencing occasional bad flareups. Throughout, she took no medications. After many challenging months, she felt better and had more energy.

She has committed to following the GAPS diet for the rest of her life. “That’s okay, though, because I am in control of my disease instead of relying on the pharmaceutical companies to be in control of it.”

She credits Gina with helping her realize that everything we put into our bodies has tremendous implications to our health. She says she is 100% sure that changing her diet saved her life.

“When I meet people who aren’t well but who complain about how hard it would be to change their diet, like going gluten free, for example,” Nora says, “I just want to grab them and shake them. I mean, you have the rest of your life. Are you going to choose to be sick, or healthy?”

It’s been ten years since Nora’s RA diagnosis. She is not 100% pain free all the time; she has good days and some bad days. She says there is still inflammation in her body, and she’s working with a chiropractor to build strength and range of motion. She has to watch that she doesn’t keep working when she’s feeling pain—a huge challenge for the nonstopping Nora.

She says she’s learned so much about how the body functions and the essential role of gut health. She’s studied micronutrients and vitamins and minerals and probiotics. Now she’s learning about that same system in the soil, and she realizes it mirrors the body systems. “It’s amazing. All life is the same!” She’s come to understand the fundamental importance of balance in all biological systems.

Nora’s journey towards health has not only brought about tremendous healing in her own body, but it has also informed a higher level of health for the land she maintains, the animals she raises and the vegetables she grows, all of which contribute to the health and wellbeing of her lucky customers.

Growing A Farm

Nora lives in the house she grew up in. If you stand facing the house, to your left is where she keeps her pigs (with a constant soundtrack of “clank” as they go in and out of their feeder). Behind you are large open areas for goats.

Off to your right is a big barn that acts as a chicken brooder and animal infirmary for young animals, and behind the barn are Nora’s vegetable garden and high tunnel. Behind and to the left of that are open fields for chickens and rolling pastures of grazing land, dotted with beef cattle. The vegetable garden is where Nora spends most of her time, unless she’s working at the farm stand or helping at the petting farm. If you drive down a path behind her house, you’ll come to her mother’s house and hay fields. The path ultimately leads you to more planting areas for flowers and tomatoes and the back of the farm stand, which faces Maryland Route 108. Down Route 108 is the petting farm. Nora zips around in her pickup from one side of the farm to the other.

Organic standards

The farm follows all the requirements of being organic but has chosen not to be certified because of the expense and paperwork of the certification process. Nora said that if she were to sell meat to a third party for distribution, she would become certified, but because she is selling directly to the consumer, she doesn’t see the need. She knows so many of her customers, and new customers are encouraged to build a relationship with the farm.

Nora takes soil samples a minimum of every three years from all over the farm, and more frequently in her garden, to ensure the soil has the nutrients it needs. She uses manure, compost, and an organic top dress that has many nutrients and minerals that help enrich and balance the nutrients in the soil. The manure from the farm animals is provides nutrients to the soil, and Nora uses it in her garden in compliance with nutrient management and food safety regulations.

In her vegetable garden, she strives to create an environment that encourages all types of bugs—good ones and bad ones. She’s found that nature has a way of keeping itself regulated. I asked specifically about bugs. “I try to keep some areas near the garden where grasses and wild flowers can grow to encourage all types of bugs. Of course it doesn’t always work out. My garden is big, but not huge, and if I have a serious infestation of a certain bug I try to hand pick them to keep the population down. I have found that larger plants can take some pest damage and it won’t hurt then in the long run, but I have had times where I needed to knock or pick the pests off a certain type of plant while the plant was young until it could get strong enough to withstand some pest damage.”

Eggs and the birth of a chicken farmer

Growing up, Nora never cared for eggs. She watched her dad devour them every day in every which way, but she thought they were awful. About a year after college and into her tenure on the farm, one of her customers at the farm stand gifted her some pastured eggs, and she tried them (“well, they were free!”). She thought they tasted good, and she became an instant convert to eggs at breakfast. Then one day someone else dropped off five chickens at the petting farm, and Nora said, “Well, why not? I eat eggs now, I’ll take some chickens!”

Before long she had more eggs than she knew what to do with, and Nora was loving them. But then—ouch—a fox got her chickens. No more eggs.

She was faced with the daunting task of going to a store for her eggs. “And I stood in front of that wall of cage-free, free-range, organic, Omega3…and I’m overwhelmed. I don’t even know what I want. And so I bought the most expensive, the most cage-free, the most Omega3-enhanced, the best fanciest ones they had, thinking that would be closest to what I had. And I won’t say that they tasted bad, but after three days of eating them, the next day I didn’t want eggs for breakfast anymore. I just found I didn’t crave them like I had. I had eaten eggs for breakfast for two months before that, so I wondered why I was off eggs now. It was weird.”

It occurred to her that her sudden lack of interest in eating eggs had something to do with the eggs themselves, and not anything within herself. It wasn’t until she tried eggs fresh off a farm again that her love-fest with eggs reignited, and she began to crave them once more. She knew that she seriously needed to get some chickens and start selling eggs in order to show everyone that there was a huge difference between store-bought and farm fresh eggs. She started raising chickens seriously in 2011.

Her mobile chicken house sits within a few fenced acres, and the chickens have their own guard dog. The dog is so sweet and friendly, it’s hard to imagine him being a good watch dog, but Nora insists he is. The chickens (and their dog) get moved around the field and into different fields as needed. The chickens forage for their food and are also supplemented with a mixture of soy-free, non-GMO grains.

How does Nora label her eggs? She said it’s a difficult topic, because there are no labeling standards. She calls them “free range” on her website, but one farmer’s free range in an open pasture might be another farmer’s free range in a big building crammed with other chickens. Just another example of the benefit of knowing your farmer.

Eggs and ? for breakfast

So what goes great with all the eggs Nora has?

“Bacon!”

The Clark petting farm has always had pigs. They acquired them by borrowing piglets from other farmers, feeding them for about four to five months while they lived at the petting farm, and then giving them back to the original owners. “Why are we doing this and then I go buy meat at the store? Why don’t I buy the piglets myself and have them grow up and be fed by the petting farm, then I get them back and process them? So I did. And it was delicious!” And went so well with the eggs.

The pigs live in the wood by Nora’s house and get rotated through the woods throughout the year. She is working on a new setup on the other side of the farm where the pigs will have access to a barn in bad weather and access to pasture as well. She’ll give the woods by her house time to rest, and then the pigs will start coming back over to the woods during the summer to forage while the pasture rests. Like the chickens, the pigs are supplemented with a free-choice non-GMO grain mixture.

Grass-fed beef

The Clark family had for generations raised beef, and when Nora’s grandfather passed away, her mom, Martha, inherited his 30 head of cattle. It was Martha who first became intrigued by what she was learning about grass-fed beef and the health benefits to humans, cows, the land, and the environment. (This is a good resource to learn more about the benefits of grass-fed.) The cattle that Martha inherited was essentially grass-fed already, but to start selling 100% grass-fed beef, the farm needed to actively expand the herd and rotationally graze the cattle over the fields to get the most out of the land and the cattle.

They sold their first grass-fed meat in 2010. The cattle are treated humanely from birth to harvest and eat grass only, with the farm’s own hay used as supplement when fresh pasture isn’t available.

Better business

At the beginning of the grass-fed beef business, the farm processed one animal about every three weeks, but each month they were selling out, and Nora was sending customers away empty handed. “And that is not good business!” So she figured if she raised more pigs, she could have some pork in the freezer to sell in addition to the beef.

And it just grew from there. She processed six pigs her first year, 20 pigs her second, and more than 30 in her third year. In 2015 she processed 40. The pig operation has really taken off, and now she sells out of her pork as well.

I was curious about the business arrangement at the farm. She told me that ever since she was a girl working at the farm stand or the petting farm, Nora was an employee of the farm. But when she started to raise her own chickens and pigs, she established herself as an LLC, and as of 2012 was officially in business for herself.

“When I was growing up, both my parents at various times of their lives owned their own businesses, and I said I would never do that. You never turn off, you never stop, you’re always thinking about it. You are the last one to turn off the lights, to check on everything. It's awful.”

“And now I’ve grown up, and I love running my own business. I never turn off, I worry about things all the time, I’m the last one to do things—but it’s satisfying. If I don’t do it, it doesn’t get done. That’s a big responsibility, but it’s also a relief in a way. If I don’t pick tomatoes and then don’t sell them, then I don’t make any money. It’s my choice to go out there and pick tomatoes. My business is my life and that’s how I want it to be now. I get out what I put in and that’s gratifying.”

Embracing the CSA model

CSA stands for Community Supported Agriculture, and it’s an increasingly popular way for people to buy their vegetables and other items directly from a farmer, and for farmers to get their products into the hands of customers. Customers pay the farmer up-front for a season’s worth of vegetables. The very idea of launching a CSA program from the farm terrified Nora. She could see the appeal for farmers who couldn’t get in to a farmers market, or were too far out for customers to come to, but Nora’s farm and farm stand are in a fantastic location, right on a main road. The thought of having to fill a share each week made her just too nervous. She was fearful that she wouldn’t have enough vegetables or enough of an assortment.

But she could also see how the CSA model could help at certain times of the year and with certain crops, and could also help with the cash flow issue at the beginning of the year when you need money for seed, planting and labor costs.

Some of the labor costs Nora speaks of. I don’t know which is more enticing: the color of the beans or the nail polish of Nora’s farm worker.

She decided to give it a try, and dove in. In 2013 she started her first season of 10 weeks with 13 members, and she admits that it was extremely hard work. Counting items, packing the boxes—it all took more time than she had expected. But she determined she would do it again the following year. Why? Because of the satisfaction she got from knowing something she grew and picked would be going home with a customer that same day.

A farm worker harvests cherry tomatoes for that day’s CSA pickup

If Nora picked lettuce, for example, to be sold at the farm stand store, she’d place it in the refrigerator and maybe it would sell by 1:00 that day and she’d regret that she hadn’t picked more, or maybe it would sell two days later. “But I don’t want to sell something two days old. I want somebody to buy it the day it’s been picked and take it home, so it’s fresh.” The CSA model assured that her vegetables went immediately from the field to the customer’s hands within a matter of hours.

Loyal customers

Nora speaks with touching emotion as she talks about her customers and how grateful she is for them. She said they have all been so patient and loyal, and she loves the bond that they’ve created. The CSA has allowed her to see her customers each week and get to know them well.

And who are her customers, exactly? Mostly families and young people in their 20s like herself who are interested in the source of their food. She also has some older customers who come in to buy meat from the store and say, “This is what meat tasted like when I was little and I was on my grandparents’ farm.”

Last summer, her third year doing the CSA, she was up to 52 shares and a 12-week season. She had 16 full and 36 medium shares and estimates that she fed about 136 people. Her goal for the upcoming 2016 season is 60 shares (30 full shares and 30 medium), again for 12 weeks.

The perfect pepper

I asked her what it felt like to provide food for so many people, and she answered by telling me about the first ripe, red pepper of the season. She knows most people’s experience of buying peppers is at the grocery store, where perfect peppers await, all neatly lined up looking lovely. The experience of buying a pepper in the grocery is unremarkable. But growing a perfect pepper is hard; when Nora’s first peppers arrive on the vine, they’ll develop spots or begin to rot before they can ripen into a beautiful red, orange, or golden color. So when the first perfectly ripe pepper appears, she gets really excited. She takes it to the stand and takes, like, 100 pictures of it to post on Facebook.

Once when she was ringing up a young couple at the farm stand, she said, “Oh you got my perfect pepper!”

“We know, we’re so excited!” they said. “It’s so beautiful, we can’t eat it tonight.” “You are whom I dream about buying this pepper!” she told them. Nora is practically jumping up and down with excitement as she tells me of their appreciation for what it took to grow that pepper. “That’s what it’s all about,” she says.

Not red like Nora’s story, but perfect nonetheless

She starts speaking even faster than she normally does as she tells me about another CSA member who loved, loved, loved the kale she got all summer from Nora. “I can’t get enough,” she said. “I’ve even gone to the store and bought the same variety you gave us. But it’s not as good.” Out of all the vegetables that Nora provided the CSA, she couldn’t believe that it was the kale that this one particular member was rhapsodizing about. “How amazing is that? But fresh, cut-that-morning kale has changed her life! It’s like my experience with the eggs. You can’t go back to the store now. You have to have the fresh.”

Happy where she is

What does Nora see for the future of her farm? She wants to hold steady at the size she is and maintain her high quality of product, but now she wants to focus on efficiency. She’s in an admirable place in terms of having help on the farm, and she’s very thankful for the wonderful people “who work really hard to make the farm great.” In the summer she hires additional part-time help, which she says she couldn’t do without.

“I need to do what makes my customers happy, but also myself. I don’t need to grow for the sake of growth. I’m good where I’m at.” Perhaps because of her health issues, but also because she’s such a wise and levelheaded person, she’s very conscious of quality-of-life issues and mindful of the issue of burning out too early.

Nora delivers vegetables picked within the hour to the farm stand for CSA pickup

It was her illness that brought her back to the farm when her chosen career in horses became impossible, and I wondered if she felt bitter about it, or if she felt she had settled when she chose a life on the farm. She replied that although she wouldn’t wish rheumatoid arthritis on anyone, she’s so happy that she is where she is now. She said she can’t imagine moving anywhere else—it would feel so strange to live off the farm. She loves being a farmer and now wouldn’t want to do anything else. “The land is there and it needs to be alive.”

Through her work at the farm stand for so many years, Nora is in a great position to notice the buying habits of her customers. She’s aware that more people have become interested in the source of their food, especially younger people, and she feels that maybe her generation, if it becomes a loud enough voice, might just be able to change the culture around food.

We can only hope, and be thankful for Nora and other farmers like her who work so hard to grow good, clean, nutrient dense food.