Hana Newcomb, Potomac Vegetable Farms, Vienna, VA - Part 1

rooted in virginia

Over 50 years ago, two people fresh out of college—he a charismatic dreamer, she in love with him and his crazy ideas—came to Washington, D.C., and started Potomac Vegetable Farms, where they grew some of the region’s best corn in various locations around Virginia and Maryland. Thanks to passion for an idea, naiveté, and ridiculous hard work, they created an enduring agricultural enterprise and a family deeply rooted in place.

Fast forward to today and an early August afternoon at the farm, where the air is full of the laughter and idle chatter of a group of young people as they hunch over their work. Hana Newcomb, second generation farmer and now at the helm of Potomac Vegetable Farms (PVF), is bent over nearby, knife in her mouth, working about ten times faster than her young workers. It’s obvious that she’s had a lifetime of experience in the fields.

Periodically their conversation is punctuated by Hana’s voice, giving instruction. “Don’t walk away from your crate. Keep it right next to you at all times. Otherwise it isn’t efficient—walking back and forth.”

The Newcomb family farm, one of the oldest continually operating farms in the Northern Virginia area, was started in the 1960s by Hana’s parents, Tony and Hiu Newcomb. We’ll hear the story of the early years in a subsequent post. The farm is comprised now of two major properties, one in Vienna a few miles up the road from the congestion and commercialism of the Tysons Corner area, and the other in Loudoun County, about 30 miles away. It seems hard to imagine as you sit in the traffic around the Tysons mall that there’s a large and quiet farm just up the road.

Farmstand, Vienna

The Vienna property is 20 acres, with about six to seven acres in production. The Loudoun County farm is 180 acres, with eight and a half acres growing vegetables and another eight and a half planted with cover crops. They rotate the crops between those acres, which Hana describes as “very deluxe. It’s not how most people get to do it. We have enough land to do that.”

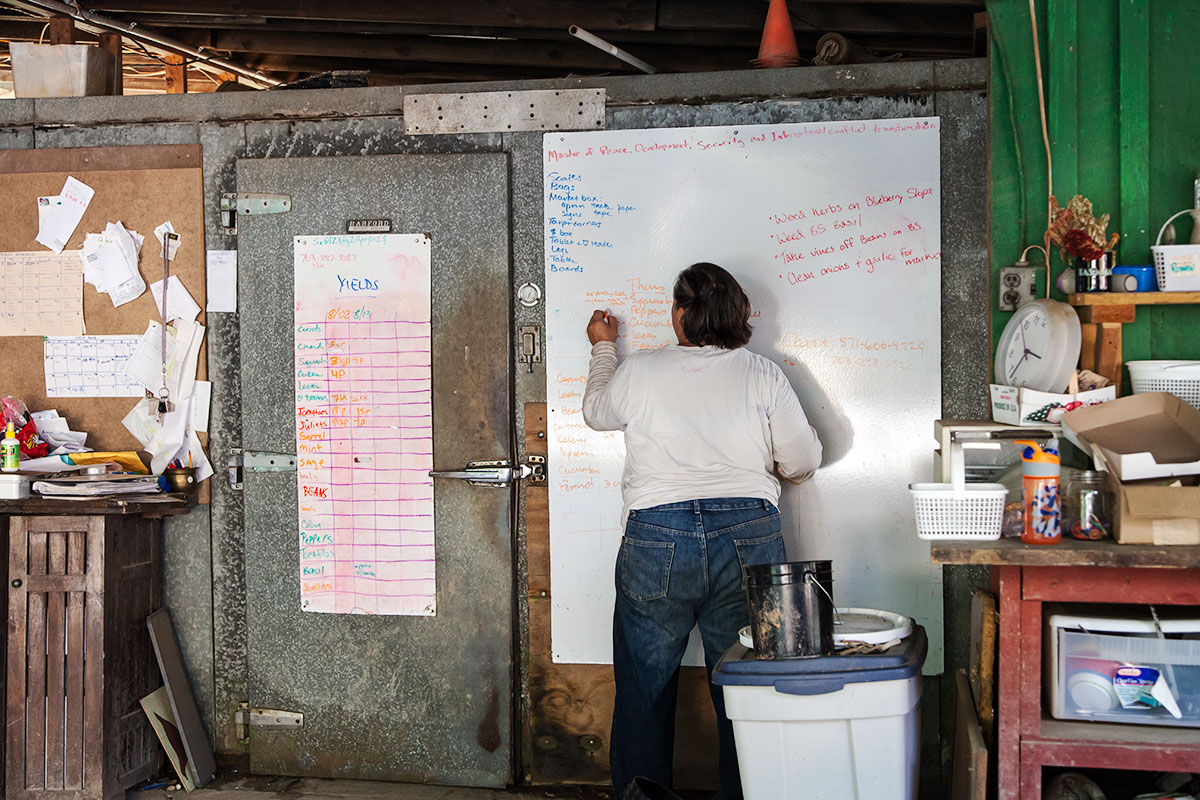

Between the two farm properties, PVF has about 500 CSA customers and sells at six farmers markets and two farm stands. Hana broke it down: “Roughly, our CSA does 40% of our business, the markets do 40%, and the two stands do 20%.” She estimates that the CSA feeds somewhere between 1,250 and 1,840 people. There are a lot of people and moving parts to the operation, all of which Hana manages with handwritten lists and schedules scribbled on a large white board in the old work area behind the farm stand.

The farm has a sizable overhead, the largest part of which is the salary the principals pay themselves, something many farms don’t do. “It’s a big business.” Hana says. “Well, it’s a big spending business, let’s put it that way. We don’t make much profit, but the profit goes into our wages. The fact that I’m getting paid means that we are making a profit.” There is a profit-sharing plan for workers who have been there longer than three years. If there is money leftover at the end of the year, the principals spread it out among the workers.

Hana attributes their success to a few different factors: being around so long, the 14 acres they have in production, their prime location, and their stick-to-it-iveness.

An intimidating clan

Potomac Vegetable Farms, and the Newcomb dynasty, have made a wide and deep footprint on their part of the world. “We are very well respected,” says Hiu, Hana’s mother, “more so than we need to be.” “Or deserve,” Hana chimes in. “We’re not visionaries,” adds her mom. “We don’t have the zeal of thinking that we know all the answers and this is the only way to be. We feel ourselves very lucky. We ended up in the vanguard of this movement that we didn’t know was happening. Tony [her husband] had the chutzpa to start this, but the whole movement thing was not very interesting to him; that wasn’t why he was doing it.”

Despite their modesty, the Newcombs come across as intimidating people. They know it, everybody jokes about it, and they even mention it on their website. Hiu, the matriarch, can seem scary, until you have a conversation with her. Maybe it’s her longevity in farming and the sense that she’s seen it all. Hana, a formidable presence, is a philosophical person with a blunt delivery system. Her three siblings wish they were like her, at least according to her sister Lani, a veterinarian. “What would Hana do in this situation?,” Lani said they ask themselves. You have the sense around Hana that there isn’t a situation that she wouldn’t know how to handle—efficiently, matter of factly, with her easy laugh and big-picture view of life. Yet as intimidating as she can appear, there’s a kind heart underneath the exterior that is sensitive to what people need emotionally. She just doesn’t coddle them.

Hiu and Hana, not so intimidating after all

Says Hana, “Every family business has a character: I think we are very welcoming to people who want to be with us, but we’re not welcoming to people who think they can tell us what to do or need a certain kind of emotional support. People need to be quite strong in order for them to fit in here. What we like is people who are very secure in who they are. And then they can do anything they want and we’ll support them.”

The crew

Each summer the farm hires a passel of young helpers (“a motley crew”), many of whom return to work at the farm each summer. “It’s not hard for us to get workers,” says Hana. “Who wouldn’t want to work for some place that’s been around as long as we have? Plus, there aren’t many farms that would take such skill-free little people,” she laughs. “There aren’t that many places where you can feel actually useful. You’re put to use and you’re part of a group that’s getting something done. That’s rare. They get so proud.”

Most of the workers are women. Says Hana, “I generally hire more women than men, and I’m pretty sure I’m allowed to do that. Mostly I prefer to hire women because they are much better workers. The way they think is closer to the way I think in terms of detail and caring about the small motor tasks as much as the big motor tasks. And most boys don’t like the small motor tasks. Most boys are just not that interested in the picky stuff. And you need to like to carry tomatoes and sort things and handle things carefully, and count, and all the things boys don’t really like to do. They like to pound things and carry heavy things and be, very, you know, heroic. Which is fine. We need those people, too.”

The farm has about 30 paid employees between the two locations, but they aren’t there every day. “I like having a different assortment of people because it makes it more interesting for everybody,” says Hana. I have an unkind but very accurate way of assessing people when they first come to work here. You tell them to do something, and you figure out very quickly how many times you have to tell them before it goes in. So then you give them a number in your head, like ‘she’s a 2, or she’s a 4′. There’s this man who worked here for years who would say, ‘I know, I know, I’m a 10.’ ” Does she give a person more than one chance? “Absolutely! And they can change their number. That’s the goal.”

The birth of a farmer

Hana grew up in Washington, D.C., but the family (Hiu, Tony, Hana and her three siblings) spent most of its time out at the farm in Vienna, traveling back and forth from the city every day. They moved out to live on the farm when she was 12 years old and had much less driving time. Summers were devoted to vegetable growing and selling. Family trips would happen in the winter, when the parents would pile all the kids into a van and take road trips that included educational or working visits to farms (not the kids’ choice of a vacation, but they did what they were told).

You have to wonder if there were any chance, given her upbringing, that Hana could not be a farmer. It wasn’t her plan, though. “I thought I’d be anything but a farmer,” she says. “I thought I was going to be a writer, or a teacher. Probably a writer, but I didn’t know what that meant. I didn’t know that that was like being an artist, and I didn’t want to be that. I realized I didn’t want to be a writer, I just wanted to write all the time. Eventually I gave up that idea.”

Hana attended Oberlin College, like every other member of the Newcomb tribe. (Seriously—just about everyone in the family has gone there; it’s where her parents met, where the children went, where many of the farm workers have gone. Hana swears it’s not a prerequisite to working at the farm.) After getting her degree in English, she moved to Boston “to go seek my fortune and be like everybody else and find out what I was going to do with my life.”

She met Jon at a contra dance. “I didn’t know he was the person for me. In fact, I told him pretty early on that I wasn’t going to marry him, because he had nothing to do with this [farming], and I couldn’t imaging marrying somebody who didn’t know about this.” Jon was totally not like anyone that people thought would be right for me. I mean, scrawny little allergic Jewish kid from the suburbs. Oh my God he was so allergic! When he came down to the farm for a visit, he thought ‘Whoa! This is pretty cool. I like this!’ He got to know my father, who told me ‘Don’t mess this up. He’s the one.’

“My father had always insisted that we all come home in the summers, so I was coming back to Virginia each of the three years I lived in Boston.” Jon really liked learning everything and just being part of the farm. I always liked it, but I just never thought I would stay. I thought you grow up and you go away, like everybody does.” But she and Jon moved back to the area when Jon got a job in D.C. as a software engineer. Hana worked at temp jobs off-season so that she could continue farm work in the summers.

Working in those offices as a temp was an eye opener for Hana. “First of all, just having to be inside and sit down and wear clean clothes and take orders from people. I behaved myself, but I kept thinking ‘Ok, you just come in a strawberry patch and you try to talk to me like that! I’ll show you who’s boss!’ It was good for me to learn that office work was not in my future. I don’t want to be bossed by somebody else. But I also didn’t have to make a commitment to the farm. No one was saying, ‘Well, are you going to do this forever?’”

Hana’s father, Tony, got sick in the early ’80s and died of lymphoma in 1984, when Hana was only 24. “So then we just never left.” She and Jon moved back to Virginia after her dad died, into a little ramshackle house with no services except a wood stove. If something needed fixing, they had to do it themselves. Jon, “not a practical, hands-on person when I met him,” loved learning how to do things.

The irony that it was Jon who led Hana back permanently the farm isn’t lost on her. “When I asked him why he liked it and the farm so much, he said, ‘If your family was a family of boat builders, I’d want to learn to build boats.’”

Hana and Jon harvesting spinach

“The idea of being back here, and making a life of it, mostly took hold after I had kids. I thought it was just embarrassing that I was doing the same thing my parents did. It wasn’t until I had kids that I thought ‘Oh, no one else is doing this. This is okay!’ And a lot of people were jealous. Because there’s no place better to raise kids than in the middle of all this. I realized it’s cooler than I understood.”

Growing into the job

In her early 20s she wasn’t in charge of the farm, “but I’d been here forever. Even a 12 year old can be in charge on the farm if they know something more than the 18 year old.” Her role on the farm evolved slowly, but it wasn’t until her mom took a yearlong sabbatical from the farm in 1993 that Hana took over the daily operation. It was then that she gained agency over what happens on the farm. Previously she was part of the team, but she wasn’t creating the direction. “It changed a lot for me to be acknowledged as somebody who is causing things to happen and to choose the workers. It’s like being the Admissions Officer.”

When her mother returned from her year away, “I just didn’t give her back the reins.”

After all these years of working at the farm, Hana still has the same level of interest and always wants to be there. “Because it’s different every year. Everything is different every day, if you think about it. The temperature, and the people you’re working with, and the places you’re wandering through. People ask me, ‘Don’t you get bored with weeding?,’ and I’m like, ‘I’m not weeding. That’s not what I’m doing. I’m making progress to the next step, whatever it is.’ People who haven’t done this their whole lives think it’s boring. But I’m doing it in order to get to the next thing. I don’t feel stuck. It’s not boring.”

In subsequent posts we’ll hear from Hiu about the wild early years of her life and the farm; we’ll hear how they’ve managed to hold on to a working farm in heavily congested (and wealthy) Fairfax County; and we’ll hear from Carrie, a co-owner who successfully established herself in the Newcomb clan about ten years ago.

Hiu Newcomb, Potomac Vegetable Farms, Vienna, VA - part 2

ORIGINS

Hiu Newcomb has spent the past 57 years pouring her hard work into Potomac Vegetable Farms, which she started with her husband Tony on cheap rental land in Northern Virginia. To hear Hiu and her daughter Hana talk about him, Tony Newcomb was an irrepressible man with an idealistic vision of creating a farm and a more just society. My sense from lots of conversation with both Hana and Hiu is that the farm owes its existence to Tony’s ideas, but it owes its survival to Hiu’s willing spirit of adventure and her commitment to the farm and her husband’s vision.

She is now the matriarch of the farm and mother to Hana, featured in Part 1 of the story of the farm.

Not mainstream

Hiu (pronounced Hugh) was born in 1935 in Honolulu to Chinese parents. At 82 years old, she has some great stories to share. For example: When she was six years old, her mother took her and her four siblings one December day to visit Santa. They stood patiently in line, while about ten miles away Pearl Harbor was being bombed. Her mother got all the kids home safely to their home on the hill, where they watched the black smoke from their living room window. They never got to see Santa.

When Hiu left home at age 17 to go to Oberlin College, to study piano and become a music teacher, she packed everything in a trunk and took a boat across the Pacific. It took five days. She landed in Los Angeles, then traveled by bus to San Francisco and stayed in a YMCA, and then took a train across country to Ohio. “It was very adventurous and wonderful.” (So different from how kids go off to college now, loaded down with all the amenities and moved lovingly into the dorm by their parents.)

I wondered if Hiu felt homesick being so far from home. “NO!” she says emphatically. “I felt liberated! I was pretty adventuresome in my youth. I did some hiking on my own. I did a lot of interesting things.”

She met Tony at Oberlin their freshman week and was smitten. “He was very charismatic. So much fun. Tony was just not in the mainstream. He was attracted to the exotic.” And she was very much in love with him. “Going back home to Hawaii after school seemed not good enough, like not enough adventure. Too predictive, and too many expectations.”

After they married, in 1958 at age 23, they came to D.C. because his parents lived here and “because it’s what Tony knew.” Hiu tried but didn’t land a teaching job. “I would have been good, but I’m glad I wasn’t a teacher.” Tony worked as a government economist, and before she had kids, Hiu worked for Tony’s father as a secretary.

And so the adventure begins

Their main transportation was a Vespa scooter. That first winter they both took off a few weeks from their jobs to visit a college friend in Mexico. It was December when they set out in a light snow on the Vespa, which had a top speed of about 35 mph. “Yeah, it was cold,” she remembers. “We didn’t have good gear. We had a sleeping bag, and we had very little money. His parents thought we were out of our minds. My parents didn’t even know. They were still in Hawaii, and my father was still grieving that I married a haole guy [Hawaiian for foreigner]. I was supposed to go home with my music education degree and teach in Honolulu and marry a nice Chinese man and be a credit to my father, who adored me and was just devastated that I didn’t come home.”

Hiu was an adventurous and free spirit. “I came into the marriage as someone independent and having a voice and I’m sure that was attractive to Tony, but he was such a dominant person. I was listening to his ideas and thinking they were great, and I wanted to be part of that life. It was exciting. Without him we couldn’t have created the things we did create. It was fun.” But along the way she lost her own voice.

Tony was always “launching into lots of things and barely finishing them,” says Hiu. He was inspired by utopian ideals of an agrarian community and wanted to grow vegetables, so they rented about 100 acres in the Tysons Corner area in 1960, before the mall was built and it became the rush-hour nightmare it is now. The land was on old dairies and was extremely cheap. “We rented it for around $15 to $20 an acre for the year. It was great rent, and the owners were so glad to have us there rather than have the land grow up in trees. They got some entertainment out of seeing us out there thrashing around. As we used that land, we raised our own rent, but I think the most we paid was $100 an acre for the year. But still that was a bargain.”

They both were still working when they started farming, but Tony had said he would quit his job when he turned 29, which he did. “He didn’t really like working in an office and not being able to take naps.” They lived in a row house in D.C. and would travel out to the land on the weekend. By this time they had graduated to a VW bug in which they’d bring the children out to the farm. This was before the beltway was built around D.C., and the trip out to Virginia was about 18 miles.

Farming was Tony’s idea, but Hiu felt part of the farm project. “Absolutely from the very beginning,” she says. “I had no farming experience; he sort of had a little bit.” And he had experience tinkering with old machinery, which served them well when they bought used equipment at farm auctions.

Sweet corn and the growth of Potomac Vegetable Farms

“My husband was trying to think of a premium crop that people would really value, and sweet corn was one of those.” They tried various ways to sell the corn, but nothing was quite working out. If they sold to the grocery store, the value of the corn was diminished by the time people bought it. “We made the decision to only sell fresh corn. Anything that was day old we would mark down. It took awhile to build up a reputation for how good the corn was.” Other farmers bought the corn to sell at their farm stands, and eventually the Newcombs established their own stand as well.

They were frugal people. “We didn’t have a lot of income. But we never defaulted on anything, and we never bought anything on credit except for the land mortgage. We couldn’t get loans through commercial banks unless Tony’s father co-signed, and his father was forever disappointed that Tony gave up his career as an economist. His father thought we shouldn’t be doing this stupid thing anyway.

“I don’t think either of us thought of ourselves as farmers. We didn’t even have a name for our farm, for maybe six years. We just thought we were trying to grow things and pay the bills. And learn stuff. We never really talked about it, we just did it.”

Tony wanted to create a community, a feeling that has passed on to Hana and her children, as we’ll hear in a subsequent post. “I think our family really likes to attract a group,” says Hana. “We like to have people around who want to do things with us.”

Who did her parents attract? For starters, a lot of young workers. From the beginning they hired young college students—many of them from Oberlin—to work on the farm. “And we paid them real money for their work,” says Hiu. They also had lots of friends. Hana recounts: “My dad would have things like the May 7 party. May 7 was the anniversary of Chairman Mao’s speech, where he said that all the bureaucrats had to go back to the land. As it turns out, the Cultural Revolution didn’t turn out so well,” she laughs, “but at the time my father thought it was awesome! Each May 7 he made all of his friends come out to the farm. It didn’t matter if it was a Tuesday or whatever, they would have to come from work to help us de-blossom strawberries or weed something. And they’d be like ‘Newcomb is crazy,’ but they’d do it because he was excited about it.”

Conventional practices

Tony and Hiu learned from their own trial and error and from visiting conventional farms on their winter vacations. “They were not the right place to go and learn these things,” she says, “but that was all we knew about. It’s not like now, where there are programs for beginning farmers. We had none of that. The Extension people had these big manuals of the pesticides we could use. We weren’t committed to being organic, because we didn’t think you could grow corn organically. So we were spraying the corn with DDT. When we grew other vegetables we used horse manure that we hauled in a dump truck from area horse barns. We didn’t know anything about soil biology, but it was a good thing what we were doing [with the non-corn vegetables]. But the corn we sprayed.”

When DDT was banned, they switched to spraying the corn with Sevin. Tony used less than the recommended amount, but he also sprayed with Atrazine and used Captan to coat the seeds. “I remember asking somebody at EPA if we had to worry about fungicides and herbicides,” says Hiu, “and they told me nah, it’s the pesticides and insecticides that you want to be more careful with. Well, Tony was going barefoot most of the time and wore no protective clothing. He mixed the stuff in a big sprayer tank, stirring it. If the nozzle got clogged he would unscrew it and blow through it.

“I think Tony always thought about the connection, and he never wanted the kids or me to get near that spray tank. He knew something wasn’t good; he just didn’t know how to do it better.”

Tony died from lymphoma in 1984.

“I think he died from 24 years of exposure to Atrazine. I read in trade journals soon after he died that there was a very strong correlation between his kind of lymphoma and that particular herbicide. And Atrazine is still being recommended and sold.”

When Tony died, Hiu announced: “ ‘We’re selling this sprayer; we’re not doing this any more.’ We were giving up using the chemicals on the corn, but it’s very hard to grow corn organically; everything wants to eat it. Everything. Birds, raccoons, bugs, worms. It’s hard to protect it. So therefore we were basically giving up the corn. We decided that even though that’s supposed to be our signature crop, we were going to move on to some other signature crop, which pretty much became tomatoes.”

They transitioned to organic and became certified in 1990, then withdrew from the certification program in 2003 when the National Organic Program came in. They call themselves ecoganic, and you can read more about their decision to forgo certification here. “We are totally committed to the principles and practices, but we didn’t think it was worth our while to gear up for the additional documentation that was required. I think it’s really important to have documentation when there’s a long chain between the farmer and the eater, but not when the chain is really short. Anybody knows that if they want to talk to us about it they can hardly shut us up about it. We’ll talk all about soil microbiology and so on.”

The theory of benign neglect

Hana was conceived on the newlywed couple’s Vespa trip to Mexico, and born in 1959. “All four of our kids were conceived on trips,” Hiu says. “In the old days we had lots of escapades. When Hana was nine months old, we took a cross-country car trip with Tony’s sister and brother-in-law. Apparently Tony decided they were going too slowly, so we got off and finished the rest of the journey by bus. Hana was traveling in a box that Tony made. Tony used to make these amazing boxes.”

Hiu was not what we now call a helicopter parent. “Benign neglect” is how she describes her parenting style. “I remember the first place we rented. It was an old house that had one bare electric bulb in each room. There was cold water but no hot water; there was an outhouse, and no houses close by. We had to be out by 6 AM to pick the corn, and the kids were not up. They were too young to leave a note—they couldn’t read. We would just leave cold cereal on the table, and they would get themselves something. It was much better when we could write a note. There were cases when their grandparents really worried whether the kids would live to grow up.

“One day, when there was just Hana and Lani, 18 months apart, we came home from picking corn, and Hana wasn’t there. Lani was barely talking, but she said ‘Hana walk’. Hana had gone off to look for us. We found her before too long, lying down in the field. She might have been 3. Another time when there were four kids, we came back and Anna and Charles were gone. They were barefoot. They had gone down the driveway looking for apples or something. Nothing bad happened, but these stories would get back to the grandparents and they’d think Oh God. We would lose the kids temporarily around the farm, but they would they eventually come back.

“I was a little bit mean as a mom,” Hiu admits. “I didn’t know what they were doing in school because they were all doing well and didn’t need me. I’m not proud of the benign neglect, but it’s good if it comes out okay.”

And did it come out okay?, I asked her. “All the kids are secure and solid,” was her reply. Says Hana to her mom, “We were fed; we were cared for. There was never a question in anyone’s mind that we were loved. You did everything that a parent needs to do.”

Hana has raised her three children with some level of benign neglect as well, “I inherited it. Part of that theory only works, though, if you have an environment that allows for it.”

Parents today might react in horror to the stories Hiu tells of her life as a mom, but when I’m around Hana and her solidity, I have to wonder about the protective way it seems most kids are being raised today (and believe me, I have been a very close-buzzing helicopter mom). My experience of the farm kids I’ve met is that they are capable little people growing up knowing how to take care of themselves. Hana says that’s true of her own children.

Separation from Tony

It’s easy to romanticize about an idyllic life on a farm. But farm life is still life, and sometimes it’s great and sometimes it’s not. Like in 1974, when the wood stove in Hiu and Tony’s house caught fire and burned off the attic and the roof. Hiu sees that fire as a turning point in her relationship with Tony, which, despite their fun adventures, had never been a wonderful match. He took up with one of the young Oberlin students who had worked on the farm in the early ’70s and moved in with her.

Hiu and Tony still ran the farm together, because they both wanted to farm. “He just didn’t want to live with me. It was terrible.” Or, as Hana characterizes it, “It was a complicated time.” It was two years later that he got sick, and two years after that that he died.

Hiu kept the farm going, with Hana’s help. After running the farm without Tony for about nine years, “it seemed to be going ok,” Hiu says. “I said to Hana, ‘I think you’ve been doing this because of me. I think that maybe this is a chance for you to think about something else you might want to do besides farming. And maybe I’ll take off a year, and we’ll just close down the farm for a year.’ I just wanted to go away for a year and then come back.

“Hana thought about it and came back the next day and said, ‘it’s kind of irresponsible to close down the farm, but I can keep it going and you can go do whatever you want.’ Hiu had been invited to do a year-long internship at Genesis Farm, an ecological learning center in New Jersey. “And so I packed up and went up to Genesis Farm. I was 58 at the time and I’ve never worked so hard in my life.

“Amazingly, the typography of that farm, the feel of the place, was so comfortable from the first day. I slipped right in and enjoyed it immensely. I just couldn’t do the work of the 20 year olds, but I did it, and it was a fantastic year in so many ways. When I came back, I didn’t know this would happen, but we changed so much of this farm. Hana had done fine. I shared what I had learned, like not plowing anymore and using different ways of planting things. We considered growing crops we never thought we could grow, like carrots and things that were more nit-picky. There were changes that we instituted over the next two years that have made the farm more what it is now. It was so important a year.”

The next adventure

Hiu had been single for ten years, and she felt pretty happy with her life. She had regained the voice that got stifled during her marriage. Farming friends introduced her to Michael, a political scientist, professor, and author, and, yes, a graduate of Oberlin College whom Hiu had failed to meet while she was there. After the dinner party where they met, Michael invited her to visit next time she was in New York, where he lived. Given that she rarely left the farm, she figured it was a pleasant evening and that was that.

A few months later, Genesis Farm (80 miles from New York City) invited her back for a week, and she invited Michael to come visit the farm, thinking he would find it interesting. They spent three days in conversation, “which I never had with Tony. So when I put him back on the bus I said ‘Thank you, Michael, this was wonderful.’ And he said ‘This is it?’ I pointed out that he lived in New York and I lived in Virginia, so yes, this was probably it.” He replied that he came down to Washington periodically for meetings, and that he’d be down there the following week.

He started coming down every other weekend, “to find out more about the farm and about me and all that.” Eight years later he was still coming down. During one of those visits, Hana asked him about his intentions. He said he’d made a commitment to her mom, but he hadn’t thought about marriage and Hiu certainly liked her independent life. Hana replied that wasn’t enough.

Michael proposed to Hiu in the Denver airport, and she made him get on his knees. She was 67 when they married in 2002. To his credit, he has successfully worked his way into the formidable Newcomb clan.

And now

Hiu has slowed down her work on the farm, but not without prodding from Hana. Says Hana, “it’s taken time to train her to do other things with her time besides farming.” She comes and goes as she pleases, which Hana plans to do when she gets older, but Hiu is still in charge of the seedlings in the greenhouse. Hana may have taken over the day-to-day operation many years ago, but Hiu is still very much a presence, zipping around the farm in the utility vehicle and seeing what her 57-year-long investment into an idea, a place, and a family has created.

Zipping around

In the next post, we’ll learn how the Newcombs have been able to hold onto all the farmland Tony and Hiu worked so hard to acquire.

Hana Newcome, Potomac Vegetable Farms, Vienna, VA - part 3

Rooted in Place

A quick recap if you’ve missed Part 1 and Part 2 of the story about Potomac Vegetable Farms in Vienna, VA, just a few miles up the road from the Tysons Corner mega-mall. The farm was started in the ‘60s by two idealistic young people, Tony and Hiu Newcomb, who through crazy hard work grew it into a profitable endeavor. Daughter Hana, who was raised both to work on the farm and to be self-sufficient, never intended to grow up to be a farmer, but never really left it. She is now at the helm.

How has the farm been able to hold onto its land, smack in the heart of rich Fairfax County and its commercial sprawl? I assumed that the farm’s 20 acres had to be worth a fortune. Well…not anymore. Thanks to another idea that the Newcombs cooked up, their farmland now has little value.

Blueberry Hill and Cohousing

“Some people think things through and make a plan,” says Hana, “but that’s just not our family. We’re more like: ‘oh, that sounds good, let’s try that!’ For example, Hana and her sister each had families of their own with small children. They lived about a 20-minute drive apart, and they were forever traveling back and forth with the kids. They wanted to live closer to each other. Their first idea was to build a house that both families would live in together. But when Hana’s sister was given a book entitled Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves, she decided cohousing was an idea worth pursuing.

Hana was game. “We can do better than live by ourselves. We can have a whole bunch of people who all want to live in this place together. So this book was like a How To manual for us. We formed a group, posted flyers and started talking about it.” That was in the mid 1990s.

The book that started it all

A group of people committed to the idea of cohousing met every Sunday afternoon for years. The idea was to take about seven acres of the farmland to create a cohousing project of 19 homes plus a common house. They named the development Blueberry Hill, and they selected a piece of land that was not in production because it was very steep and wooded. “Without knowing anything,” says Hana, “we built the houses on this steep place, which has actually turned out to be much more interesting than living on a flat place.

“We didn’t have a developer. It was just us, and you need a lot of money in order to do this.” It was a $4 million project. They had feasibility study conversations with many people, and luckily ended up hiring an architect who was intrigued by the project. After months of working together, he asked, “Do you think I could join?” His house was partly paid for by the work he did, and he still lives in it. Group members each put in $20,000, which would be a down payment on a house if the project worked. If it didn’t work, they’d lose their $20,000. Many of Hana’s family members bought in.

“We were just clueless! We were doing our best just to figure out the next thing.”

It may not have been their first intention, but by creating Blueberry Hill, Hana and family ensured that the farmland would remain such by taking the development rights off of it. In Fairfax County, where the farm is located, zoning plans are based largely on how many houses are on the property next to you, so that the area looks coherent. Zoning has to meet the needs of the people next door, so whenever you want to change the zoning of your land, you have to get past your neighbors. The developer of the land adjacent to the farm did something a little different when he took a 100-acre property and clustered the large homes closer together on 50 acres and left 50 acres open for parkland and flood plain. So even though the property is zoned for one house per acre, each house doesn’t sit on its own acre.

Some of the homeowners in that community objected to the Blueberry Hill plan, fearing that the small footprint of the homes would bring down their property values.

But the Blueberry Hill gang had based their model on exactly what their neighbors had done (cluster the homes close together so the farmland would remain open), and they were able to win zoning approval from the Board of Supervisors.

Says Hana, “When the county created PDH-1 [one house per acre], that wasn’t the picture in their mind. They didn’t think about people like us, because we aren’t normal, but now we have all this open farmland that we barely pay any taxes on at all because it doesn’t have any building rights on it. It has very little value. It wasn’t like a strategy; it just how it ended up being. We took advantage of something that already existed.” She laughs, “When you gather up a group of people in Northern Virginia who want to do something and who are smart and thoughtful—well, together somebody figured this out.”

The homes were ready for occupancy in 2000. Everyone owns their own house, but much of the land and the common house are communally owned. Everyone pays dues, and community members do most of the work themselves.

The development is designed for residents to see each other, and they grow close. “It’s very village-y.” There are only pedestrian walkways through the development. Residents park their cars near the common house entrance and walk to their houses (carts are available to help transport groceries or whatever). The common house is where residents gather for weekly community meals, meetings, and access to things like games and movies. And what’s right down the hill? A farm! Residents can take a nice stroll down the hill for fresh veggies, milk, eggs, and other goodies Hana keeps stocked in the farm store.

“You can’t take a picture of me sitting down! I never sit down to pick spinach!”

“We like that we’ve taken away the value of the place,” says Hana, “because it means we can stay. People have stopped sending us letters saying ‘I’ll buy your property for $10 million.’ It doesn’t happen anymore, and it’s great. We don’t have to interact —we’re invisible now. Nobody in Fairfax County even thinks of this as farmland anymore. We’re the only ones. And all the people who buy houses around here think this is terrible soil. Universally they’ll say ‘I have really bad soil on my yard’ and I’ll think, ‘Well we all know why that is, it’s because it got scraped off when they built your house and they left you with a lot of subsoil. But we don’t have that problem. We don’t scrape our soil off and it’s been building up for 50 years.”

Rich soil that will remain farmland

She loves being able to keep the farm where it’s been located all these years (“The schools! The library! Plays!”), and she’s a natural for the cohousing experience. “I don’t think everyone necessarily gets along, but we are all committed to getting along. When you come here you kind of know what you are getting into. It’s a welcoming place. But apparently there are a lot of unwritten cultural things that people have to figure out. It’s getting complicated because half of the old group is gone, and new people have to get used to it.”

Staying put

When Hana speaks, she often speaks as a “we” and not an “I”. She’s been part of a close-knit family and a farm community her whole life, and she radiates an enviable sense of rootedness and belonging. “When you get old and people start dying, you start thinking ‘How did I make the choices in my life that allow me to be where I am today?’ One of the reasons for the choices we’ve made, I think, is because our dad died when he was very young. [Tony was 48 and Hana was 24.] I think that weathering that taught me about how important it is to be surrounded by people I’ve known a long time. And to stay in one place.

“The whole practice of staying in one place, which doesn’t happen very much, has made us really resilient as a family. We live near each other, and it’s very nice to know people intimately and to know them for your whole life. To live in a place where you’re not starting over all the time, and when the people are coming to you and joining your group, instead of you always trying to reestablish identities. We know who we are, and we know we live here, and if you want to be here, we’d love to have you too.

“And so I think that was a lesson that’s taken me a long time to understand about what we got out of my dad dying. We got a lot of things out of it, but one of the things was learning that you can survive that. People learn from the things that happen to them, and that’s what we learned. Like, ‘Stick it out!’ I worry about families that are so spread out, and so disparate. It’s not very secure; there aren’t so many givens when you’re all spread out. Like I know families that don’t even do Thanksgiving. I’m like, ‘What do you mean you don’t do Thanksgiving?’ At what time do you get together?’ You have to do something every year in order to make a solid ritual.”

As she speaks, I’m reminded of her father’s insistence that the kids return to the farm each summer. And her father’s annual May 7 parties, when he pressed all his friends to come work on the farm in honor of Chairman Mao’s speech that called for all bureaucrats to return to the land. Hana makes frequent reference to her dad, the charismatic, enthusiastic, wild-idea man with a dream of an agrarian community. “He had the chutzpah to do this,” Hana’s mom Hiu says. And it’s Hiu and Hana and all the people they’ve brought together who have had the stick-to-it-iveness to grow that early dream into an enduring farm and housing community.

Stay tuned to meet Carrie, a “recent” addition to PVF (ten years ago) and now a co-owner.